telemetR: Creating an Animal Movement Database

20 Dec 2016The first post in the telemetR series, creating a PostgreSQL database to store animal movement data.

- The Problem

- A RDBMS Solution

- Up and Running

- Creating the Database

- Data Flow

- Wrap it Up

- Telemetr Series

The Problem

A general outline of deploying and managing telemetry data is as follows.

- Capture the animal and put the device on. Record the device ID and animal ID so these two can be associated later.

- Download the GPS data from the vendor. If the device is a store-on-board wait till the collar falls off the animal, get the collar then download the data.

- Store the data in a spreadsheet within a folder labeled with the animals or devices ID. Each new download of data is stored in a separate spreadsheet (common practice based on my experience).

- When the collar deployment is finished combine all collar data for that animal into a comprehensive spreadsheet. Name it

xxxID_final_version1.5.xlsx. - Run analysis for this animal.

- To look at all data from certain population categories:

- Lookup animal ID and categories to group the data.

- Find those animal’s spreadsheets and copy & paste that data into one. Name it

population_area1_females.xlsx&population_area1_males.xlsx, etc. - Redo step 6.1 and 6.2 each time you need to change the data.

- Load the data into R or a GIS software. Manually fix errors in the data. Do this for the comprehensive data files, but redo it every time those comprehensive files need to be fixed (it isn’t changed in the raw data, or it is forgotten).

- Exploratory data analysis and visualization.

Maybe I’m being a little harsh, but I’m sure we all know someone that would manage their data this way. Good data management is hard and often overlooked. Especially when job duties or daily tasks are more urgent or important apparently.

A RDBMS Solution

I set out to build a system that would take the hard parts out of the data management. Almost all of the redundant and extraneous work can be accomplished with an aptitude for technology and basic coding skills. Even better all this is can automated and served as a fairly simple application that allows anyone to do it. My long term goal is to develop this system. I’ve laid the ground work the the telemetR application. Now I need to work on the backend and data entry portions.

Data Model

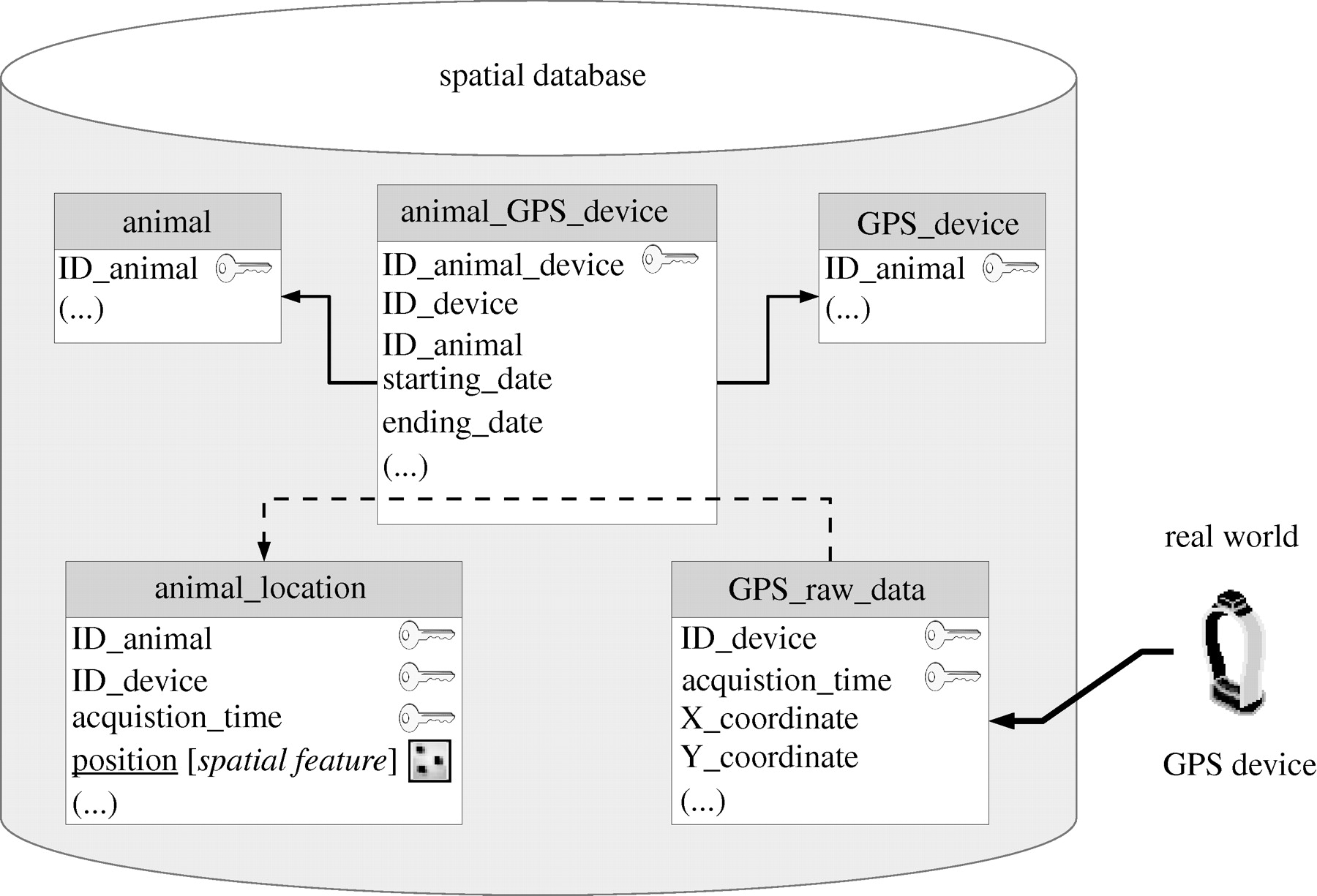

Figure 1. From Urbano et al. (2010): General representation of a possible standard database data model for core wildlife GPS data. When the GPS device provides coordinates of a location at a specified time, they are uploaded in the database in a table (GPS_raw_data). A device is associated to an animal for a defined time range (table animal_GPS_device, connected to the tables animal and GPS_device with foreign keys, represented by solid arrows in the figure). According to the acquisition time, GPS-based locations are therefore assigned to a specific animal (i.e. the animal wearing the device in that particular moment) using the information of the table animal_GPS_device. Thus, the spatial table animal_location is filled (dashed arrow) with the identifier of the individual, its position (as a spatial object), the acquisition time and the identifier of the GPS device.

The core data model is heavily influenced by Urbano et al. (2010). The caption above does a good job explaining how this model combines animal and raw GPS data into a set of GPS data (trajectory) for each animal. Getting here is the hard part.

Up and Running

Lucky for me Urbano wrote/edited a book about building a database for animal tracking data. Unfortunately it is expensive (If you have institutional access to Springer you may be able to download with that). The first 4 chapters are a step by step tutorial on setting up the relational database. Chapter 5 introduces the spatial components of PostgreSQL (PostGIS). Chapter 6 onward explains how to leverage the capabilities of postgres/PostGIS to build a full data management system and incorporate R and GIS software. I will loosely follow this book to design the backend of telemetR. I will make modification where I see fit so the database is more easily accessible by a variety of technologies that I use.

I will assume anyone following along has a basic knowledge of SQL commands. If you need a refresher I highly recommend PostgresSQL Tutorial. A future post will focus more on SQL; we need a working database first.

Installing PostgreSQL

Installing PostgreSQL depends on your operating system . I use a Mac and used homebrew to install PostgreSQL (install homebrew). Perhaps the easiest solution for Mac is to install the Postgres.app. For other operating systems check the official documentation. A final option is to use a database as a service (DBaaS). An option for postgres is ElephantSQL. The latter will be useful if you want other users to have access to the data. For this entire tutorial series I’m going to assume that you will be working on a local instance of postgres.

Creating the Database

The data model from figure 1 will guide the development of the database. We will create 5 tables, animals, devices, deployments, raw_gps, and telemetry. The first step is to create a database with the createdb command then connecting to the database with psql.

createdb telemtry

psql telemetryAnimals Table

Each animal that gets a collar will go in this table. Data associated with this animal, such as age and sex, will be stored here as well.

-- step 1

CREATE TABLE animals (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

perm_id varchar(20),

sex varchar(8),

age varchar(10),

species varchar(4),

notes varchar,

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

updated_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

deleted_at timestamp with time zone

);

-- step 2

COMMENT ON TABLE animals IS 'Animals catalog with the main information on individuals.';

-- step 3

INSERT INTO animals (perm_id, sex, age, species)

VALUES

('4416', 'female', 'adult', 'sp1'),

('4584', 'female', 'sub adult', 'sp2');

-- step 4

SELECT * FROM animals;

\d animalsStep 1 creates the animals table. In this table we will store the permanent animal id (perm_id), the sex, age, species, and any notes associated with the animal. The sex, age, and species fields will be limited to 8, 10, 4 characters respectively. The created_at, updated_at, deleted_at fields are timestamps that default the timezone the server is in. I use these fields so that I know the timestamps that a recored is created, updated, or deleted; they will be in every table. The deleted_at field is optional, but allows for a “soft” delete of a record. The record will still exist, but it can be excluded from any SELECT or UPDATE statements. The id field is a running sequence of numbers and the PRIMARY KEY of this table. Every record will have an id. We can use this number to reference an animal in other tables.

Step 2 adds a comment to the table and is good practice. I’ll exclude this step from future table statements. This step is essentially the same for every table. I’ll exclude explaining this step unless it is necessary.

Step 3 & 4 inserts some data into the table. Notice fields that are declared as characters are in quotes. In the next step I select all (* is a shortcut for all) of the data from the animals table. Then I use \d to list the fields and information of that table. I’ll do this for every table just to see that it was created correctly. I’ll exclude these commands from future code blocks.

We can include lookup tables for the species and age fields and reference them with their respective ID’s from those tables. We will leave them as is and update them later when we create the lookup tables in a future post

Ideally each perm_id will be unique and be used on only one animal. Sometimes this isn’t practical. For instance, we’ve used large survey tags with alpha codes to identify animals. Sometimes these can be duplicated in different areas of the state or in differenct species.

Devices Table

The devices table will be a catalog of every device that we have purchased and plan on deploying. Each device is entered only once in this table. Redeploying devices will be addressed in the deployments table.

-- step 1

CREATE TABLE devices (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

serial_num character varying(50) UNIQUE,

frequency real,

vendor character varying(50),

device_type character varying(50),

mfg_date date,

model character varying,

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

updated_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

deleted_at timestamp with time zone

);

-- step 2

INSERT INTO devices (serial_num, vendor, device_type, mfg_date)

VALUES

('360662', 'northstar', 'gps', '2010-01-01'),

('13528', 'vectronic', 'gps', '2013-01-01');The field names here are fairly self explanatory. The serial_num should be unique, and no two devices should share the same serial number. The UNIQUE tag will only allow unique values to be inserted into this field. The frequency is of class real, which means a decimal number.

Deployments Table

This table is where things start to get interesting. The deployments table will keep track of which animal has which collar and the period of time that those collars are deployed.

-- step 1

CREATE TABLE deployments (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

animal_id integer REFERENCES animals(id),

device_id integer REFERENCES devices(id),

inservice date,

outservice date,

created_at timestamp with time zone default now(),

updated_at timestamp with time zone default now(),

UNIQUE (animal_id, device_id)

);

-- step 2

INSERT INTO deployments (animal_id, device_id, inservice, outservice)

VALUES

(2, 2, '2016-04-01', '2016-04-05'),

(1, 1, '2011-03-10', '2011-03-15');The big change in this table compared to the previous two is the REFERENCES tag. This tells postgres that the value of this field should be in the referenced table(field) (a foreign key). For instance, the animal_id is referencing the id field in the animals table. The raw data from this table (SELECT * FROM deployments;) returns data that isn’t very useful, especially once there are hundreds of deployments in the table. The foreign keys in this table lets us write a SELECT query to grab the animal’s perm_id and serial_num from the animals and devices table.

SELECT animals.perm_id, devices.serial_num, deployments.inservice, deployments.outservice

FROM animals, devices, deployments

WHERE

deployments.animal_id = animals.id AND

deployments.device_id = devices.id;

-- alternatively

SELECT animals.perm_id, devices.serial_num, deployments.inservice, deployments.outservice

FROM

(deployments INNER JOIN animals ON deployments.animal_id = animals.id) INNER JOIN

devices ON deployments.device_id = devices.id;First, the two queries above return the same data:

perm_id | serial_num | inservice | outservice

---------+------------+------------+-----------

4584 | 13528 | 2016-04-01 | 2016-04-05

4416 | 360662 | 2011-03-10 | 2011-03-15Second, this seems like a query we might run a lot, why not just put the perm_id and serial_num in the table to begin with. There is a possibility that two animals may have the same perm_id. Sometimes study design comes second (or is ignored). I find that having the database autonumber and reference those numbers leads to fewer human mistakes.

Because this is a query we might want to look at frequently we can save it as a view. A view is essentially a saved query within the database. There are a few different types of views (refer to this), we are going to create a simple view. The view will always be up to date, even if new data is entered.

CREATE VIEW animal_device AS

SELECT animals.perm_id, devices.serial_num, deployments.inservice, deployments.outservice

FROM (deployments INNER JOIN animals ON deployments.animal_id = animals.id) INNER JOIN devices ON deployments.device_id = devices.id

ORDER BY deployments.id DESC;

SELECT * FROM animal_device;Third, because of the foreign key constraint on both the animal_id and device_id fields, those fields must exist in the database. Try entering a deployment with a device_id or animal_id of 3. The database will throw an error describing why the data wasn’t entered.

ERROR: insert or update on table "deployments" violates foreign key constraint "deployments_animal_id_fkey"

DETAIL: Key (animal_id) = (3) is not present in table "animals"GPS Tables

The raw GPS table will hold GPS data from the devices without the id from the animal table, and time frames outside the deployment dates. The data will also hold some quality control data that isn’t used in data analysis. The fields in this table may vary depending on the vendor of the devices. There isn’t a standard format that vendors are required to report their data in. The following is based on the raw data I get from Lotek and ATS.

CREATE TABLE raw_gps (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

serial_num character varying(50) REFERENCES devices(serial_num),

acq_time timestamp with time zone,

activity real,

latitude real,

longitude real,

easting integer,

northing integer,

altitude real,

hdop real,

pdop real,

temperature real,

n_satelites integer,

fix_type character varying(25),

status character varying,

gps_volts real,

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

updated_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now()

);The telemetry table will have parsed GPS data that includes the animal_id and only data between the deployment dates.

CREATE TABLE telemetry (

id serial PRIMARY KEY,

raw_gps_id integer REFERENCES raw_gps(id),

animal_id integer REFERENCES animals(id),

device_id integer REFERENCES devices(id),

acq_time timestamp with time zone,

latitude real,

longitude real,

easting integer,

northing integer,

utm_zone integer,

altitude real,

hdop real,

pdop real,

temperature real,

n_sats integer,

fix_type varchar(10),

status varchar(25),

main_v real,

back_v real,

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now(),

updated_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now()

);Data Flow

To review, we have tables to store animals, devices, and deployments as well as tables to store the raw and parsed GPS data. At this point our database will manage which animals have which collars, when they were deployed and when that deployments ended. The data should flow in the following order.

- New devices are added to the devices table when they are ordered

- An animal is capture, a device is deployed, and the animal data is entered.

- The deployments table is updated with the proper IDs (we will automate this in a later post) and

inservicedate. - When the deployment ends the

outservicecolumn is updated to the proper date. - GPS data is uploaded to the GPS table. This triggers a function to insert parsed data into the telemetry table.

Upload Collar Data

Now the fun part, lets upload the collar data (grab the csv here).

COPY raw_gps (serial_num, acq_time, longitude, latitude)

FROM '/Users/mitchellgritts/Dropbox/Data/telemetr/gps13528.csv'

WITH (FORMAT csv, DELIMITER ',', HEADER true);

-- check that it was properly imported

SELECT serial_num, acq_time, longitude, latitude FROM raw_gps;The raw_gps table doens’t associate an animal with the GPS data, and contains points outside of the deployment date. There Are several reasons why points may outside these dates. For instance, an animal dies and several days pass before the collar can be picked up and turned off. Or the collar may be turned on prior to the actual deployment and collect points while en route to the location an animal is captured. Notice that the start and end dates are 2016-03-30 and 2016-04-06 while the deployment dates for this collar were between 2016-04-01 and 2016-04-05. We can see the devices_id and animal_id from the deployments table by running the query below.

SELECT

deployments.device_id,

deployments.animal_id,

raw_gps.acq_time,

raw_gps.longitude,

raw_gps.latitude

FROM

deployments, raw_gps, devices

WHERE

raw_gps.serial_num = devices.serial_num AND

devices.id = deployments.device_id

ORDER BY

animal_id, acq_time;Great, but we still have data outside of the deployment dates. To limit to the deployment dates we need to add another statement to the WHERE clause.

SELECT

deployments.device_id,

deployments.animal_id,

raw_gps.acq_time,

raw_gps.longitude,

raw_gps.latitude

FROM

deployments, raw_gps, devices

WHERE

raw_gps.serial_num = devices.serial_num AND

devices.id = deployments.device_id AND

(

(raw_gps.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

raw_gps.acq_time <= deployments.outservice)

OR

(raw_gps.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

deployments.outservice IS NULL)

)

ORDER BY

animal_id, acq_time;Insert Collar Data into Telemetry Table

The next step is to insert this data into the telemetry table. We need to make sure we only import points that occur during the deployment and assign the animals.id to each record. To do this we can use SELECT query above in the INSERT query.

INSERT INTO telemetry (raw_gps_id, animal_id, device_id, acq_time, longitude, latitude)

SELECT

raw_gps.id AS raw_gps_id,

deployments.device_id,

deployments.animal_id,

raw_gps.acq_time,

raw_gps.longitude,

raw_gps.latitude

FROM

deployments, raw_gps, devices

WHERE

raw_gps.serial_num = devices.serial_num AND

devices.id = deployments.device_id AND

(

(raw_gps.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

raw_gps.acq_time <= deployments.outservice)

OR

(raw_gps.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

deployments.outservice IS NULL)

);

-- see the results!

SELECT id, raw_gps_id, animal_id, device_id, acq_time, longitude, latitude

FROM telemetry

ORDER BY acq_time;

-- get the real animal and device id's

SELECT

animals.perm_id,

devices.serial_num,

telemetry.acq_time,

telemetry.longitude,

telemetry.latitude,

telemetry.created_at

FROM telemetry, animals, devices

WHERE

telemetry.animal_id = animals.id AND

telemetry.device_id = devices.id

ORDER BY acq_time;Awesome! The raw gps data is parsed and inserted into the telemetry table. We can query the telemetry table and join it with the animals and devices tables to get analysis ready data! I created a new view with the above SELECT query.

Automate GPS Data Flow

Instead of running the select every time we upload new data is added we can use a trigger to insert new data into the telemetry table.

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION raw_gps_to_telemetry() -- 1

RETURNS trigger AS

$BODY$ begin

INSERT INTO telemetry (raw_gps_id, animal_id, device_id, acq_time, longitude, latitude) -- 2

SELECT

NEW.id AS raw_gps_id,

deployments.device_id,

deployments.animal_id,

NEW.acq_time,

NEW.longitude,

NEW.latitude

FROM deployments, devices

WHERE

NEW.serial_num = devices.serial_num AND

devices.id = deployments.device_id AND

(

(NEW.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

NEW.acq_time <= deployments.outservice)

OR

(NEW.acq_time >= deployments.inservice AND

deployments.outservice IS NULL)

);

RETURN NULL;

END

$BODY$

LANGUAGE plpgsql VOLATILE

COST 100;

-- 3

COMMENT ON FUNCTION raw_gps_to_telemetry()

IS 'Upload new data in raw_gps to telemetry table';

-- 4

CREATE TRIGGER trigger_gps_data_upload

AFTER INSERT

ON raw_gps

FOR EACH ROW

EXECUTE PROCEDURE raw_gps_to_telemetry();

COMMENT ON TRIGGER trigger_gps_data_upload ON raw_gps

IS 'Insert new data into the telemetry table when a new record is added.';

-- (5) now test that this works by uploading new data

COPY raw_gps (serial_num, acq_time, longitude, latitude)

FROM '/Users/mitchellgritts/Dropbox/Data/telemetr/gps4416.csv'

WITH (FORMAT csv, DELIMITER ',', HEADER true);

-- 6

SELECT id, serial_num, acq_time, longitude, latitude

FROM raw_gps

WHERE serial_num = '360662';

-- 7

SELECT animal_id, device_id, acq_time, longitude, latitude

FROM telemetry

WHERE device_id = 1

ORDER BY acq_time;Breaking down the code block above:

- Create a function that we can call on the trigger. Read more about triggers

- The INSERT query that will run when the trigger is called. This is the same INSERT query we used to insert data into the

telemetrytable the first time. - Comment the function.

- Assign the function to run as a trigger when new records are added to the

raw_gpstable. I commented the trigger as well. - Upload some new GPS data to test that the trigger runs when data is inserted into

raw_gps - Check the newly updated data in the

raw_gpstable. - Check that the data new data was inserted into the

telemetrytable.

Wrap it Up

You should hava a fully functioning RDBMS to manage collar data. The database we’ve set up closely resembles the data model from Urbano et al. (2010). There are a few minor changes between them. Data should first be entered into the animals and devices table. Once that data is entered animals can be associated with GPS devices in the deployments table. GPS data can be uploaded to the database and will be automatically parsed and inserted into the telemetry table in a format that is ready for analysis. In the next post we will extend the PostgreSQL with the spatial tools from PostGIS.

Telemetr Series

- Introduction

- Creating an Animal Movement Database

- Extending the Database with PostGIS

- Connecting to the Database with R

- Adding More SQL Functionality

- Shiny Web Application

- A Simple RESTful API

- … more